How Overempowerment Leads to Underachievement*

Children with above average and gifte d abilities may mystify their parents and teachers by doing poorly in school. They have the capabilities to do well, yet they may be disorganized, avoid homework and study while blaming their poor achievement on boredom, teachers, parents, other children, or even the dog. While there are many complex contributing causes of underachievement, one problem I often see at Family Achievement Clinic is overempowerment. Children who have been given too many choices, too much power or too much freedom too soon, either at home or school, are at high risk for underachievement. They become so accustomed to making decisions about their lives that they assume they should always make all their own choices. Thus, when teachers require assignments, they may oppose them because they want personal control. Underachievement in school may result from children’s assumptions that they should control all their own learning

d abilities may mystify their parents and teachers by doing poorly in school. They have the capabilities to do well, yet they may be disorganized, avoid homework and study while blaming their poor achievement on boredom, teachers, parents, other children, or even the dog. While there are many complex contributing causes of underachievement, one problem I often see at Family Achievement Clinic is overempowerment. Children who have been given too many choices, too much power or too much freedom too soon, either at home or school, are at high risk for underachievement. They become so accustomed to making decisions about their lives that they assume they should always make all their own choices. Thus, when teachers require assignments, they may oppose them because they want personal control. Underachievement in school may result from children’s assumptions that they should control all their own learning

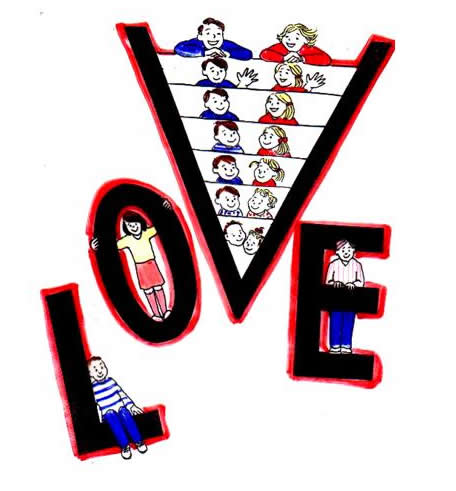

The V of Love

Children require leadership and limits to feel secure and to achieve. Envision the letter V. When children are small, they’re at the base of the V and should be given few choices, little power, and small responsibilities that match their size. As they mature, they need increased choices, freedom, power and responsibilities. Childhood and adolescence can be relatively smooth if children are, thus, gradually empowered.

If you reverse that V like this—Λ—and children at home and school are given too much power and freedom and too many choices, they may be empowered too early. They may resent rules and responsibilities and feel as if parents and teachers are taking away their freedom when they set reasonable requirements or limits. They expect to be treated as adults before they’re ready. In adolescence, ordinary limits cause them to become angry, depressed and rebellious because they feel powerless compared to the power they experienced too early.

It’s unfair to treat children as adults too soon. They feel more secure and confident if they gradually earn adult status. Certain children are more likely to be “adultized” than others: gifted children, only or oldest children, youngest children born after siblings are grown, and children of single or divorced parents.

Children’s verbal giftedness increases the

My parents won't listen to me. My dad thinks I should be treated differently because I'm a kid. I want the same treatment as my parents. He says, "I'm the adult here and I should be treated differently because I'm older." I don't agree. 5th grade boy |

likelihood of adultizement because very bright children often display advanced vocabulary, reasoning skills, and sensitivities that cause parents to assume that they have wisdom beyond their ages. While they may actually be more mature than their age-mates, they aren’t likely to be as mature as they sound. They require the opportunity to play out a reasonable childhood. They are children first, gifted only second.

Only children and oldest children are frequently treated like one of the adults in the family and become accustomed to equal adult status, and sometimes, more than equal power. Single parents and those undergoing divorce frequently choose one child, usually their oldest, as confidant and partner. They may consult with the child about major life issues and replace the closeness and intimacy that they would normally have with a spouse with their relationship with this favored child.

Adultized children gain the social, intellectual, and apparent emotional sophistication that emerges from a close and enriched experience with their parent. They may, however, suffer from the feelings of insecurity and powerlessness that emerge with too early adult power. In classroom and peer relationships, if they aren’t given control, they may feel “put down” or disrespected in comparison to the way in which they’re regarded at home. They actually feel “disempowered,” relative to the feelings of being in control at home.

Dethronement

The most difficult risk of adultizement is “dethronement.” When another sibling is born or if the adultized child isn’t recognized as special in the class, he may feel irrationally and extraordinarily rejected. Dethroned children typically exhibit negativity, anger, or sadness. They may readily be labeled depressed, anxious, or ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder). Their personalities may change so dramatically that parents, teachers and even doctors may assume they’re undergoing clinical depression.

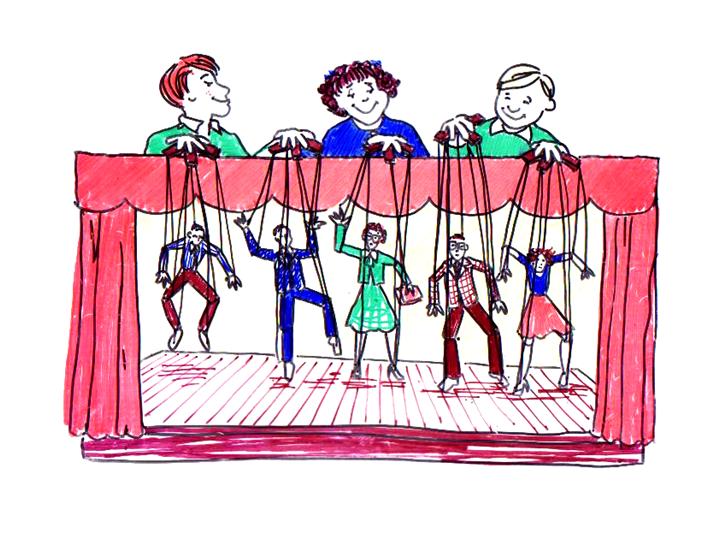

A dultized children may try to run their families, their teachers, and other students, and they may argue incessantly and believe that if they provide sufficient reason, they are always right. They say, “Why would I argue unless I was right?” Their parents often refer to them as “lawyers.” They may enjoy arguing with teachers more than learning from them. As they trap adults into the battles, parents and teachers find themselves losing their tempers. “How did this happen?” they ask themselves. “How can that 10-year-old believe he can run the entire family?” “Why does that 12-year-old assume his teacher knows nothing?”

dultized children may try to run their families, their teachers, and other students, and they may argue incessantly and believe that if they provide sufficient reason, they are always right. They say, “Why would I argue unless I was right?” Their parents often refer to them as “lawyers.” They may enjoy arguing with teachers more than learning from them. As they trap adults into the battles, parents and teachers find themselves losing their tempers. “How did this happen?” they ask themselves. “How can that 10-year-old believe he can run the entire family?” “Why does that 12-year-old assume his teacher knows nothing?”

Teachers and parents, offended by such powerful children, try to “put them in their places.” Adults respond to these dictatorial, offensive children with a big NO permanently engraved on their foreheads. “Unfair,” the children argue, undaunted. They believe that no one understands them and, indeed, almost no one does.

Teachers and parents, offended by such powerful children, try to “put them in their places.” Adults respond to these dictatorial, offensive children with a big NO permanently engraved on their foreheads. “Unfair,” the children argue, undaunted. They believe that no one understands them and, indeed, almost no one does.

Parent Advocates

Parents need to be advocates for their children's education because they often understand their children's educational needs. Schoolwork could be too easy for gifted children or too difficult for children with disabilities. Either may lead children toward underachievement. When teachers differentiate curriculum, students can learn to enjoy appropriate challenge and learning in school.

RIMM’S LAW I

Children are more likely to be achievers if their parents join

together to give the same clear and positive message about

school effort and expectations.

Communication between home and school can be delicate but needs to be handled respectfully, particularly since children watch parents and teachers as role models. If children hear parents negate their teachers in the name of challenge, children may easily assume that they should be able to skip assignments because they're too easy or that their teachers don't know how to teach them. If they hear parents describing teachers as expecting too much, children will assume that the work is too hard and will give up. Children are easily overempowered by hearing their parents criticize teachers. They soon assume that they can pick and choose what work they consider appropriate and can skip assignments they decide they'd rather not do. They may develop patterns of avoiding their schoolwork, when in fact they worry that they won't be able to accomplish it to the standard expected of them.

Dependence and Dominance

Children may exhibit too much power in either dependent or dominant directions or both. Dominant power is easily identified in aggressive children who want to monopolize attention or in those who argue endlessly. They’re almost immediately viewed as too powerful.

Dependent children who manipulate their adult world in ways that say, “Take  care of me, feel sorry for me, make things easier, help me, or protect me” aren’t usually recognized as powerful. The children’s symptoms of power (tears and requests for pity) are very persuasive, so parents and teachers continue to protect them, unintentionally stealing from them their opportunities to cope with challenge. As a result, these children don’t develop sufficient self-confidence to build the independence that fosters achievement and accomplishment.

care of me, feel sorry for me, make things easier, help me, or protect me” aren’t usually recognized as powerful. The children’s symptoms of power (tears and requests for pity) are very persuasive, so parents and teachers continue to protect them, unintentionally stealing from them their opportunities to cope with challenge. As a result, these children don’t develop sufficient self-confidence to build the independence that fosters achievement and accomplishment.

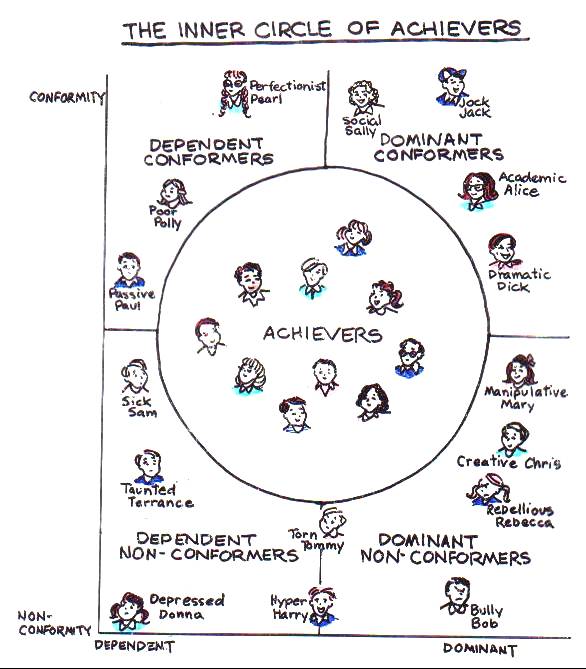

The Inner Circle of Achievement

The children in the inner circle are achievers. They’ve internalized the relationship between efforts and outcomes. That is, they persevere because they recognize that their efforts make a difference. They know how to cope with competition. They love to win, but when they lose or experience a failure, they don’t give up; instead, they try again. They understand that winning and losing are temporary and don’t view themselves as losers.

They don’t view themselves as failures but only see some experiences as unsuccessful and learn from them. No children (or adults) remain in the inner circle at all times; however, the inner circle represents the predominant behavior of achieving children. Outside the circle are prototypical children who represent characteristics of underachievers. These children have learned avoidance and defensive behaviors to protect their fragile self-concepts because they fear taking the risk of making the efforts that might lead to less-than-expected performance.

The children on the left side of the figure are those who have learned to manipulate adults in their environment in dependent ways. Their words and body language say, “Take care of me, protect me,it’s too hard, I need help.” Adults in these children’s lives listen to their children too literally and unintentionally provide more protection and help than the children need. As a result, these children get so much help from others that they lose self-confidence. They do less, and parents and teachers expect less. They quietly slip between the cracks, neither they nor their parents or teachers recognize the capabilities that were exhibited earlier or on tests.

On the right side of the figure are dominant children. These children only select activities in which they feel confident they’ll be winners. They tend to believe that they know best about almost everything. They manipulate by trapping parents and teachers into arguments. The adults attempt to be fair and rational, while the dominant children attempt to win because they’re convinced they’re right. If the children lose, they consider the adults to be unfair or mean. Once they establish adults as unfair, they use that enmity as an excuse for not doing their work or taking on their responsibilities. Furthermore, they manage to get allies on their side against the adult. Gradually, the children increase their list of adult enemies. They lose confidence in themselves because their confidence is based precariously on their successful manipulation of parents and teachers. When adults tire of being manipulated and respond negatively, the dominant children complain that adults don’t understand or like them, and a negative atmosphere becomes pervasive.

Appropriate Empowerment

In granting children appropriate power, we must give them sufficient freedom and power to provide them with the courage for intellectual risk-taking. However, we should also teach sufficient humility so that they recognize that their views of the world aren’t the only correct ones. Although we need to empower them enough to study, learn, question, persevere, challenge, and discuss, we cannot grant them so much power that they infringe on parents’ and teachers’ authority for guiding them. That authority is, indeed, more fragile for this generation’s children than it has ever been.

*Parts of this article are adapted from Why Bright Kids Get Poor

Grades (Crown Publishing, 1995) and How to Parent So Children

Will Learn (Crown Publishing, 1996) by Sylvia Rimm.

©2005 by Sylvia Rimm, President, Educational Assessment Service, Inc. W6050 Apple Rd, Watertown WI 53098. 800-795-7466

All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the author.